TRADE LINKS IN THE EASTERN HINDU KUSH: THE CHITRAL ROUTE

Written by Prof. Hermann Kreutzmann

The paper was presented in the Third International Hindukush Cultural Conference 1995 and is being reproduced here with courtesy to the author

Introduction

Approaching Chitral, the present-day visitor is confronted with the cul-de-sac situation of one of the largest districts of Pakistan. Chitral’s communication and traffic links are virtually reduced to only one major road connecting Chitral with Peshawar. This circumstance is especially felt during the cold season from October to May when the Loari Top (3118 m) is practically impassable. A number of enterprises have been envisaged to link Chitral and its dispersed villages with modern traffic infrastructure. The Kunar Valley Road could be an alternative all-year-long approach from the south, but it crosses through Afghan territory.Presently this road is not safe for all kinds of traffic. Plans for a tunnel underneath the Loari Top are regularly discussed; drilling started in the 1970s but came to a sudden halt shortly afterwards and was never commenced since. The strategic importance of the Lutkoh valley for the supplies of Afghan mujahiddeen (holy warriors) has improved the traffic infrastructure towards the Dora Pass. The Shandur Pass Road is presently upgraded and different contractors-national and international-are involved in sections of this corridor, which eventually could provide Chitral with a truckable connection leading to the Karakoram Highway (KKH). Nevertheless, the present situation seems to be a reflex on Chitral’s strategic position within international boundaries contiguous to neighbours of different political alliances. In this study, it is attempted to draw attention to a certain historical period prior to the closure of international boundaries and the introduction of motorized traffic when Chitral commanded a trade corridor for commerce with Central Asia.

Central Asian Trade Competition and Routes of Exchange in the Nineteenth Century

During the ‘great game’ played between Russian and British diplomats, special attention was directed towards regions outside their direct sphere of control such as the urban oases of Kashgaria, where a strong competition for market domination arose. Access to these Chinese-dominated cities and turntables of Central Asian trade was easier from the Russian railhead at Andijan than from British India. The mountain barrier of the Hindu Kush, Karakoram, and the Himalayas posed a major obstacle to modern traffic, that is, railways, in the second half of the nineteenth century. From the end of those lines caravan trade based on mules, horses, camels, and human porterage was the only feasible option. The distance between Andijan and Kashgar could be covered in twelve marches by crossing only the Terek Dawan (3870 m).

Trade caravans from British India were channeled through three routes. All of them were much longer and involved the hardship of crossing major mountain passes. The longest but most important route was the Leh corridor, involving fifty marches between Srinagar and Yarkand by covering a total distance of 1706 kilometers from the railhead in Rawalpindi to Kashgar. Five passes above 5000 meters had to be crossed in addition to numerous river fordings. The caravans needed to carry fodder and supplies for fourteen consecutive marches. Reaching for the same destination, the route via Gilgit was much shorter. The 1335 kilometer-long sector afforded only twenty-nine marches between Gilgit and Kashgar and the passage of two passes of minor difficulty. Problems abounded in the Hunza valley, where frequent fording of rivers and difficult passages along the notorious hanging paths restricted the volume of trade. This route regularly imposed heavy losses on the traders. Meager resources on route resulted in shortages in fodder supply, but one of the biggest problems was the extraordinarily high demand in toll taxes and grazing fees by the rulers of Hunza and Nager. Their cupidity affected the reputation of this trade corridor as well. The Chitral route remained the shortest thoroughfare of all by covering a distance of 1169 kilometes between Peshawar and Kashgar. Here the major uncertainty was the dependence on good relations with Afghanistan as the territory of the neighbouring country had to be crossed on the route to and from Central Asia (cf. Harris 1971). This feature proved to be a shortcoming and created many reservations by traders and administrators.

Assets and Constraints of the ChitralRoute

On the route via Chitral the railhead at Dargai was the starting point for British Indian goods on their journey towards Kashgar. It took forty marches for mule and/or horse caravans to cover the distance. From Chitral Bazaar, the valley was followed north and in Mastuj the route turned up the Yarkhun River (cf. Younghusband 1894, 1895). Crossing the Boroghil Pass (3807 m) on the border with Afghanistan the caravans proceeded to Sarhad-e-Wakhan.Here,the Wakhan and Chitral routes united. In the direction of Kashgar, the traders proceeded through the Pamir-e-Khurd (Little Pamir) andcrossed Kirghiz grazing grounds towards the Wakhjir Pass (4923 m) where they left the Afghan-controlled Wakhan Corridor. Entering the Taghdumbash Pamir and Chinese territory, the Chitral route linked up with the one from Gilgit. From Mintaka Aghzi in the Kara Chukur valley both continued via Tashkurgan to Kashgar and Yarkand respectively. The Chitral route proved to be faster than the Gilgit and Leh routes by a span of two days to nearly three weeks.

Depending on favourable political relations with Afghanistan, the narrow transit sector posed a vulnerable trading corridor. Between 1897 and 1904 the Afghan government attempted to deviate the Chitral trade to another sector. After Amir Abdur Rahman Khan’s conquest of Kafiristan (nowadays Nuristan), he attempted to display territorial control by leading a trade route from Faizabad to Parun, Asmar, and Bajour which involved twenty-nine stages without major obstacles (Holzwarth 1990: 199). In the aftermath, Anglo-Afghan relations deteriorated again with a culmination in the 1919 war. This struggle terminated British domination and finally led to Afghan sovereignty. Although Chitral militia supported British forces during this war, the Afghan government kept an interest in continuing trade via Badakhshan and officially acknowledged the Chitral route in 1920.On this route varying custom duties were leved on different commodities: export of pistachio nuts (50 %), cumin (40 %), sheep and opium (30 %), woollen fabrics, and animal skins and hides (10-20 %). The import duties of consumer goods ranged between 100 per cent for luxury items, 40 per cent for tea, and 15-22 per cent for cotton and sugar (Ghani 1921:250-61 quoted in Holzwarth 1990: 202). The political developments, additional custom duties, and the insecurity of trade-as much in the so-called tribal areas of Dir and Bajour as across the boundaries–counterbalanced the timesaving aspect on this route, which was only seasonally open in the summers. Even the lower unit cost, that is, the fact that the average transport fees for standardized pieces of commerce were lower than those on any other route, could not make up for this and draw substantial quantities of trade volume.

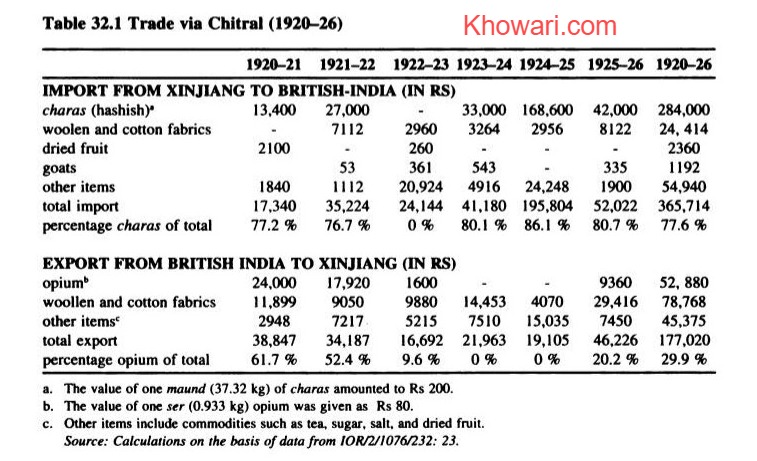

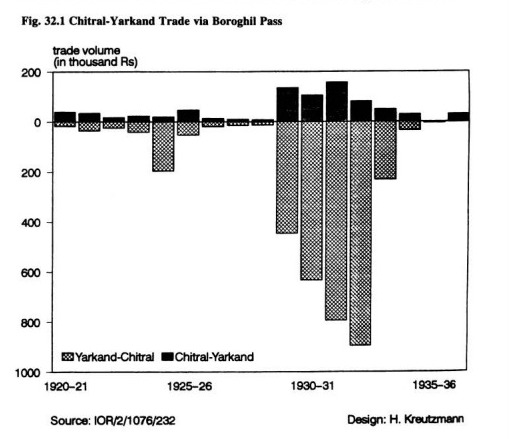

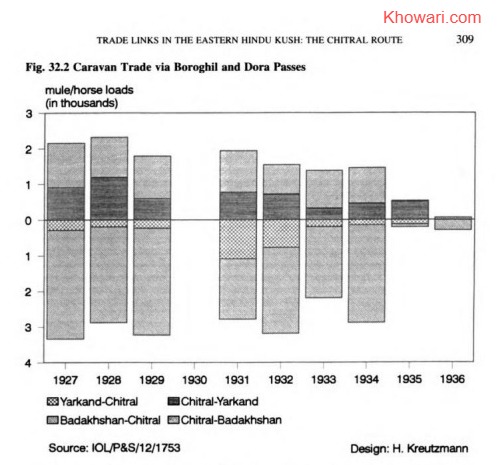

All the same, the trade via Chitral fluctuated during this period in a manner that Chitral held a share of 34.6 per cent in 1932 of the total Central Asian trade volume which was reduced to only 0.2 per cent four years later(Figs. 32.1 and 32.2). Looking at different trade items, we see a regional peculiarity emerge which is connected with the commodities exchanged. While in the overall Central Asian trade the import of Xinjiang charas (hashish, Cannabisindica) ranged around a fifth of the total, the charas trade via Chitral accounted for more than three quarters in the 1920s (Table 32.1). Besides officially accepted drug trade by licensed dealers, a certain share was smuggled in order to avoid the payment of taxes and custom duties to Chinese, Afghan, and British authorities. For this specific purpose, the Chitral route had an additional advantage compared to other thorough fares. The overall volume might have been much higher taking into account the observation by Skrine (1925:234) in the 1920s about’…Chitrali and Badakhshi traders who smuggle Yarkand charas (hemp drug)into India and Afghanistan through Chitral, and Afghan opium into Kashgaria on their return journey. ‘Comparing the commercial costs for 1931 reveals that the charas import to British India via Chitral was about 19 per cent cheaper than via Leh. This calculation includes all transport charges, taxes, and customs duties. The difference was significant for charas, felts,and animal skins while the import of silk was cheaper via Leh.’

The persons whom Skrine identified as traders and smugglers from Chitral and Badakhshan covered only one part of the business. Licensed drug dealers involved in this profitable

enterprise originated mainly from Hoshiarpur (Punjab) and Shikarpur (Sindh). Expanding their business, these Hindu traders were also engaged in money-lending. Along all trade routes they controlled a transborder network of financial institutions. When a new bazaar was built in Chitral in 1904, the British political agent

…advised the Mehtar to set aside a certain number of shops for Hindus. There is at present only one shop owned by a Hindu in Chitral, and the introduction of some competition of this sort would tend to break the ring of Bajauri Parachas [small merchants] who at present have matters too much their own way.2

Like other enterprises, this trade was interrupted due to the disturbances in Xinjiang in the 1930s as well. While some of the established downcountry traders continued for a while with colonial support, Chitral was already out of licensed charas trade as the transit corridor through Afghanistan was no longer feasible. All Xinjiang charas entered British India via Leh, the little that was left before the closure of the borders and the expulsion of traders.

In the other direction (south-north) about 30 per cent of all export via Chitral (Tab. 32.1) was commanded by opium (teryok, Papaver somniferum). This cash crop gained in importance as an export commodity of Badakhshan in the beginning of the twentieth century.Holzwarth (1990: 206-14) attributes this development to two factors: first, in 1907, Anglo-Sino negotiations about opium trade had led to an agreement about the gradual reduction of exports to China; second, Xinjiang gained more detachment from core politics after the Chinese Revolution of 1911. Thus, a power and economic vacuum furnished favorable conditions for making opium sales by satisfying the continuing demand of Chinese users. As this trade was mainly dominated by Badakhshanis and Pathans from Bajour and the Malakand Agency, the Chitral route played an important role. The British consul-general stated the developments:

The Sinkiang authorities have been making strenuous efforts during the past few years to eradicate the opium traffic and heavy penalties are imposed on Chinese subjects found to be in possession of opium. In the past, the opium traffic in South Sinkiang has been chiefly in the hands of Afghans and Pathans of Indian territory (especially of Bajaur and the states of the Malakand Agency) and the activities of these Pathans have to some extent been partly responsible for the anti British attitude of the Sinkiang authorities. These men have been making use of their status as ‘British protected persons’ to escape the consequences of being discovered in illegal activities but they have persistently ignored orders and warnings issued from this Consulate-General forbidding British subjects to have any dealings in opium.

The fact that Pathan and Badakhshani traders operating on the Chitral route were mainly involved is somehow surprising as the production zone of charas was far away from Chitral in the Yarkand and Khotan districts, and to a limited degree in Russian/Soviet Turkestan.Other routes would have been closer, but the advantage was the lower burden from taxation and customs, thus increasing the trade profits. While in tsarist Middle Asia the export of charas was prohibited since the beginning of the twentieth century, Xinjiang experienced a similar declaration in 1909 in connection with the opium legislation of the central government in Beijing.4

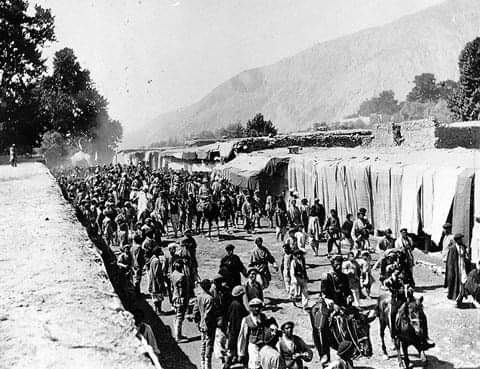

Besides these lightweight and valuable drugs, items such as woollen and cotton fabrics,dried fruit, and livestock products constituted some of the commodities exchanged via Chitral Bazaar.Here,traders from Afghanistan and Central Asia met with those of the south.The Norwegian linguist Georg Morgenstierne observed in 1929:

From beyond the Hindu Kush passes a constant stream of traders comes down to Chitral. The two most important passes are the Dorah in the north-western, and the Baroghil in the north-eastern corner of Chitral. But communication with the north is by no means restricted to these comparatively easy passes, and in spite of snow-blindness and dangers many lightly equipped travellers use the higher and much more difficult passes to the north of the Dorah in order to save a day or two. But these passes have scarcely ever been used by invaders.

Across the Baroghil came Wakhis, but chiefly traders bring blocks of reddish rock-salt and lapis lazuli [lazurite] from the mines belonging to the Afghan government,but exploited by the local population during the rebellion in 1929. Chitral is a local emporium of some importance in these regions. [p. 31:There is no bazaar in Chitral above the capital]. While several caravans from Badakhshan carrying rugs, Russian china etc. passed through Chitral on their way to Peshawar,the local traders from Munjan and neighbouring valleys rarely go further than Chitral, but dispose of their goods there.5

The importance of this trade can be estimated by comparing the state income derived from this sector with other sources and by looking at the groups participating in it. The only central place for these enterprises was located in Chitral proper. Consequently, it is not a surprising fact that the state authorities played an important role in it.

The Mehtar of Chitral’s Revenue and Income from Trade

The Lockhart and Woodthorpe mission visited Chitral in 1885 and estimated the sources of state revenue. According to their observation the ruling families played a significant role in the trans-border trade and had managed to monopolize certain activities:

The Mehtar of Chitrál derives his income from the following sources:-

1. The sale of timber and orpiment [auripigment, As, S,]to foreign traders.

2. The sale of lead to Bájaorí traders, and of lead and gold-dust in the country.

3. Slave-trade.

4. Toll on horses and all pack animals passing through from Badakhshán to Dír, Bájaor,and Pesháwar, and vice versa.

5. A fixed contribution of sheep, goats and grain, rugs, choghas and tsadars from each province [regional sub-unit of Chitral].

6. Tribute from Káfiristán, and fines imposed on the subject Kalásh Káfirs,&c.

7.The Kashmir subsidy.

He also barters English piece-goods and other merchandise from Péshawar. such as tea in Badakhshán for Yambús, or Yárkand ingots of silver. He further takes his pick of the horses brought from the north for the southern markets. The traders consequently have taken to hogging the manes of their best ponies,which disfigures them in Chitrál, but does not interfere with their sale in Pesháwar.’

Tolls-These are numerous and vexatious to the traders passing through the Mehtar’s territory.He himself takes the proceeds of a few stations, but his sons and favoured officials are allowed to take toll at many others.

The rates fixed at Chitrál for horses, &c.. laden or unladen, passing through from foreign countries and returning,are as follows:-

Per 1 horse-2 Kábal rupees. Per I mule-I Kábal rupee. Per 3 asses-I Kábal rupee. (Lockhart &Woodthorpe 1889:266-67)

What were the major sources of income? Basically there were two important ones according to their list: exchange relations with non-local traders, and taxes levied in Chitral. This dual structure of state revenue underpinned the significance of external relations and commercial endeavors. As the hereditary ruler of Chitral had to satisfy the demands and needs of a growing number of relatives in different parts of his state these sources became the more important. At that time, the mehtar of Chitral received an annual subsidy from Kashmir to the value of Rs 3600 on top of his income from these sources (Lockhart & Woodthorpe 1889:268). His allowance was raised later on and in 1889

…the Mehtar of Chitral was granted a subsidy of Rs 6,000 per annum and a large consignment of rifles. In 1891 the Government of India, with the intention of strengthening the position of the Mehtar, decided to double this subsidy on the condition that he accepted the advice of the British Agent in all matters relating to foreign policy and the defence of the frontier. (Malleson 1907:43).

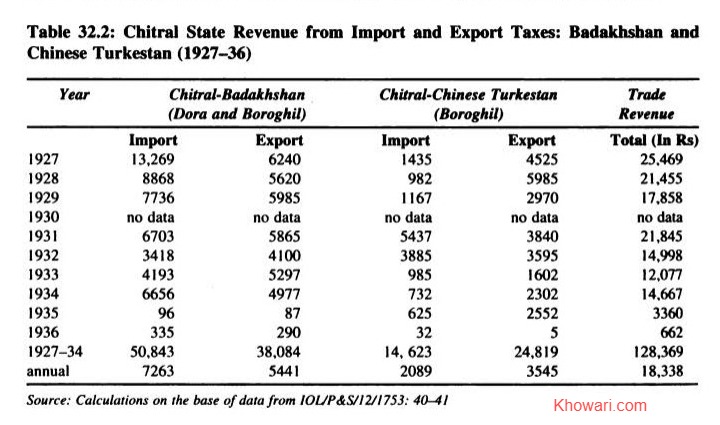

In comparison with the British-Indian support, the mehtar of Chitral managed to derive a similar revenue from tolls on trade which accounted for Rs 33,397 averaging Rs 6679.40 per annum between 1896 and 1901.6 The sources of income developed and continued to move upward in a similar manner, and in 1906,’…Mehtar Shuja-ul-Mulk receives a subsidy of Rs.1,000 per mensem and an annual allowance of Rs 8,000 as compensation for the loss of the Mastuj and Laspur districts’ (Malleson 1907: 79). From 1927 to 1936 the mehtar of Chitral accrued Rs 136,413 in import and export taxes from traders in Chitral. Those were the ‘good’ years when the contribution from trade dues amounted to Rs 18,338 per annum on average (Table 32.2). Although data is scanty and needs to be supplemented with explicit lists of internal sources of state income, it can be concluded that a substantial contribution to Chitral’s state revenue was derived from exchange relations with entrepreneurs. This factor is often neglected when the political structure of Chitral is explained only on the basis of internal and land-related social hierarchies. The centre of power based its overall control of the state on its wealth extracted from the rural areas as much as from pecuniary resources supplied by traders. The predominantly non-local businessmen used Chitral as an important entrepot. For them, Chitral Bazaar was a central place for the exploitation of trade niches. Chitral held a favourable position in relation to consumer places and resource areas such as Badakhshan, Xinjiang, and the NWFP.

The share of the local people in any surplus from trade and subsidies indicates that little trickled down. Their exchange with traders was basically restricted to the supply of porterage. In addition, some barter trade in fodder and food for consumer goods occurred. As part of their obligations local farmers had to be available as load-carriers (coolies) for the porterage of state goods. The residents functioned as labourers for the maintenance of tracks and bridges under the ubiquitous scheme of forced labour (kar-i-begār,rajaaki) for the ruling class, a constellation which could be observed in neighbouring mountain societies as well. Thus, a relationship developed in which the external resources such as subsidies, octroi, and customs duties helped to stabilize the centre of power. From the colonial perspective indirect rule in the form of installing and supporting a mehtar or mir had led to the direct transfer of state subsidies to loyal chiefs. The right and procedures of internal distribution and allocation of funds was reserved under their sole authority. In a similar manner revenue from trade was mainly accumulated at the seat of power. From the perspective of the local population forced labour in the form of porterage, provision of supplies, and infrastructure construction and maintenance was taken for granted or without remuneration, thus enhancing the wealth of the local rulers. Consequently, the socio-economic gap between centre and periphery within the mountain societies widened by providing a traffic infrastructure for external or imperial interests and non-local entrepreneurs. The limited spin-off effects of developments such as the provision of roads and bridges for inter-village communication and limited marketing and exchange of locally produced goods should not be omitted.

The End of Chitral’s involvement in Central Asian Trade

The sudden interruption of trade made felt the mutual dependence: the purchase of local grain and fodder by itinerant traders had provided a welcome local market for the mountain farmers in need of bartering for salt, tea, and other consumer goods such as kitchenware and cotton cloth. For the well-to-do, luxury items were available in Chitral Bazaar only. Overall trade declined significantly in the mid-1930s after the Afghan government’s decision to inflict a

trade embargo on Chitral. The pretext for terminating exchange relations in this trade sector was the alleged illegal import of charas into Afghanistan and uncontrolled export of gold and lapis lazuli. Consequently, Chitral’s trade corridor with Xinjiang was cut off as well. The mehtar of Chitral,Shuja-ul-Mulk, assessed the importance of exchange relations:

Our flourishing timber trade which was the chief source of income during my father’s time has been totally prohibited. The Afghans are… bent upon ruining our trade… have been looking on us as a thorn in their side, and by imposing prohibitive taxes on the Sarhadi Wakhan,they have stopped the trade between this country [Chitral] and Yarkand… This year they have practically closed all the Badakhshan routes to all the import and export trade with Chitral.”

The British political agent in Malakand reported to his superiors about the situation in Chitral and emphasized on the fiscal effects and the survival conditions for the local population:

…The country [Chitral] is being very hard hit by the restriction on trade over the Dorah and Baroghil Passes imposed by the Afghan Government…practically all trade has ceased between Chitral and Badakhshan and Wakhan. It is a very serious matter for the Chitral State revenues and also for the inhabitants of Northern Chitral the livelihood of many of whose inhabitants depended on this trade.Salt was a most important import from Badakhshan and its stoppage is causing great hardship.The Afghans of the provinces concerned mustalso be feeling the loss of their trade with Chitral…Afghanistan is trying to bring pressure on Chitral to use the Kunar valley route only with possible development of this route to facilitate traffic.°

The following months did not bring any improvements in the bleak situation, and in 1936,trade performance had reached the bottom line. Income from trade contributed to Chitral’s state revenue only a meagre 3 per cent of the value which had been generated five years earlier (Table 32.2). The entrepreneurs in Chitral trade filed a petition which was presented through British diplomatic channels: ‘The traders of Chitral wish to be allowed to import the following from Badakhshan: Pistachio nuts, caraway, almonds, salt, opium, dried cheese, lapislazuli, carpets, namdahs, cloth (khaddar), cloth (silk), pattis and chogahs, skins and wild animals (stone marten, fox and panther), sulpher, wool, sheep and goats.’1° All efforts did not significantly improve the situation and failed to restore bilateral exchange relations. On a lower level, some trade continued by smuggling of goods across the border passes; especially by this method substantial quantities of opium reached Chitral annually (Holzwarth 1990:205-06).Besides the unilateral Afghan termination of trade caravans across the Boroghil and Dora passes, internal developments in Xinjiang attenuated the prospects. Overall, a significant decline of all trade between British India and Central Asia followed.

Response to Trade Decline and Border Closures

The commencement of the Cold War and the subsequent Chinese Revolution resulted in the closure of international boundaries and mountain passes and amplified the decline on all sectors. Central Asian trade via the Chitral route had come to an end already in 1935. This turning point marked the beginning of a domestic response to the loss of goods exchange. Parallel to the trade decline and the growing restrictions of the Xinjiang authorities on the export of charas,the cultivation of this valuable cash crop was promoted in Chitral. As a new source of income generation it replaced the revenue loss accrued out of trade decline and served a continuing

demand in British India. After the Chinese borders were sealed in 1950/1951, the superior quality products from Xinjiang ceased to be a competitive commodity on the market. This event further boosted charas cultivation in Upper Chitral. Staley (1966: 234) measured the share of revenue accounted for by taxes on charas production in the order of one third of the total.The cultivation zones in Chitral range from 1760 meters to 3350 meters inaltitude and are located in Lotkuh, Torkhow, Mulikhow, and Yarkhun. Licensed cultivation was permitted in Swat and Chitral while charas cultivation was prohibited in the Gilgit Agency. The total export of charas from Chitral was estimated at 500 maunds (18,516 kg) in 1964. A state sales tax of Rs 5 per pound ofcharas was levied within Chitral while an additional export tax of Rs 11.50 per pound had to be paid when it left the state.”‘ Other estimates highlighted its importance in the state’s trade balance by attributing 80 per cent of all exports to charas in the 1960s.!2 The introduction of this cash crop can be perceived as a direct resuIt of trade decline and response to vanishing economic opportunities.

Potentials and Prospects

The case of Chitral has been presented as an example of the termination of international trade and domestic responses. While its decline coincided with the factual closure of all three South Asian approach routes perpetually, plans have existed to reopen the thoroughfares if political conditions permit. This medium-term perspective gains in importance as political conditions have been affected by recent developments. How has Chitral prepared itself for commercial exchange with independent Central Asian republics? This consideration has to be evaluated on the basis of infrastructure assets and sectors of surplus production.

The infrastructural factor is tied with the closure of the Chitral route. The economic attraction and potential of Chitral itself has not been able to sustain further improvements in order to improve the link to downcountry Pakistan. Prior to partition only the road between Ashret and Chitral Town was widened for motor vehicles. Those had been carried in pieces across the Loari Top and mechanics reassembled them at the location.The Loari Pass remain-ed a serious obstacle until 1947, when the first jeep managed to cross. From then onwards a regular service between Dir and Chitral came into being but was restricted to the summer months.” The road from Chitral via Mastuj to Sor Laspur was improved in a manner that motorcycles could ply between Chitral and the foot of the Shandur Pass (Power 1948:70).A shuttle service was introduced between Drosh and Chitral where approximately forty vehicles were in use to link the two central places. Dichter (1967: 47) mentions that this service included the connection of Chitral with the only airport (in Balach since 1951; Ghufran 1962:268) at Drosh serviced twice a week. In 1962, Chitral Airport was inaugurated with daily flights, weather conditions permitting.Considerable extensions of jeep tracks were commissioned after partition when Chitral State acceded to Pakistan. By the mid-1960s the road network within the cul-de-sac of Chitral had increased five times.’4

All these developments do not disguise the fact that the loss of Chitral’s function as a highland entrepot for cross-boundary and transmontane trade affected the traffic situation detrimentally and was connected with a slow growth of infrastructure. The previously central position of Chitral Bazaar had been converted into a cul-de-sac position at the end of an exchange corridor. Henceforth, Chitral’s economic relations were totally directed southwards,a change which found its political expression by terminating the area’s special constitutional status and in the abolishment of the state in 1969. The short-lived advantage of being a

commercial turntable in the Hindu Kush has never come back to Chitral since. This has had an effect on the district’s economy.

For comparative purposes, it might be suitable to state that the availability and sale of consumer goods in Gilgit District is much higher than in Chitral District. The total value and per capita supply of consumer goods from downcountry Pakistan is only less than a quarter in Chitral (Kreutzmann 1995: 220). All the same, the demand for the import of rice,wheat flour,and grain is quite substantial in Chitral, an area where agriculture overshadows all other economic activities. The import of these basic foodstuffs across the Loari Pass covers about three-quarters of the value of all goods purchased. The still growing dependence of Chitral on external supplies involves high costs for carriage as the Loari Pass remains a major physical obstacle and the Kunar Valley Road insecure.

While in the beginning of this century different modes of transport were applied for sustaining international trade, the present technology of motor vehicles leaves little scope for alternative routes as the cost of road construction in mountain areas exceeds the allocation in public budgets by far. This fact is symbolized in the Loari tunnel project, which was planned for two decades and commenced in the 1970s but stopped soon after.

NOTES

1. The Afghan authorities levied a transit tax of Rs 21 per pony-load of silk at the customs check-post at Sarhad-e-Wakhan while the same quantity of charas passed through for Rs 4.50 (IOL/P&S/12/3246:India Office Library & Records: Departmental Papers: Political & Secret Internal Files & Collections 1931-1947: Chinese Turkestan:Trade: Development of Trade between India and Chinese Turkestan. Letter of Consul-General Kashgar 11.7.1931).

2. IOL/P&S/7/165/1054: India Office Library &Records: files Relating to Indian States Extracted from the Political and secret letters from India 1881-1911:Chitral Diary 30.4.1904.

3. IOL/P&S/12/2358: India Office Library & Records: Departmental Papers: Political & Secret Internal Files &Collections 1931-1947: Letter from H.H.Johnson, Consul-General Kashgar to Government of India, Simla, dated Kashgar 15.8.1940.

4. IOL/P&S/7/240/923: India Office Library & Records: Files Relating to Indian States Extracted from the Political and Secret Letters from India 1881-1911: Memorandum of Information… May 1910. The date given was 21.11.1909 for implementing this legislation. In the following year it was reported that this prohibition act had not immediately affected opium and charas cultivation at all (IOL/P&S/7/242/1367: India Office Library & Records: Files relating to Indian states extracted from the Political and Secret Letters from India 1881-1911: Memorandum of Information August 1910).

5. Morgenstierne 1932: 31-2. Faizi (1991: 188) mentions the establishment of a bonded warehouse in Boroghil (Yarkhun) in 1926 in order”…to check the illegal import of charas.’

6. IOL/P&S/7/136/982: India Office Library & Records: Files Relating to Indian States Extracted from the Political and Secret Letters from India for 1908.Vol.8.

7. Cf. in this context the descriptions of Chitral’s social structure and taxation system by Barth (1956:80-83); Beg (1990: 7); Eggert (1990); Lorimer (1980: 224-29). Biddulph (1880: 66) already mentions the importance of trade for the state revenue of Chitral.

8. IOL/P&S/12/1753: India Office Library & Records: Departmental Papers: Political & Secret Internal Files &Collections 1931-1947: Afghanistan. Trade. Stoppage of Trade between Chitral and Badakhshan: Rough Translation of the Persian Speech delivered by His Highness Sahib of Chitral…in the Durbar hed in Chitral on 6th of Oct., 1935:pp. 94-96.

9. IOL/P&S/12/1753: India Office Library & Records: Departmental Papers: Political & Secret Internal Files &Collections 1931-1947: Afghanistan.Trade.Stoppage of Trade between Chitral and Badakhshan: Memorandum on ‘Chitral Trade’, P.A. Dir, Swat and Chitral, Malakand 15.10.1935:pp.90-91.

10. IOL/P&S/12/1753: India Office Library & Records: Departmental Papers: Political & Secret Internal Files &Collections 1931-1947: Afghanistan. Trade.Stoppage of Trade between Chitral and Badakhshan: Memorandum from the Political Agent Dir, Swat and Chitral, Malakand 26.3.1936:p.64.

11. Data provided by the Chitral state revenue authorities,quoted from Staley 1966:234.

12. Dichter 1967: 45. A significant share left the state as contraband; legal export was restricted to the so-called ‘tribal areas’ alone.

13. Proudlock 1947:193-94. Cf. for the development of traffic conditions prior to partition Schomberg 1938:24.29;Power 1948; Staley 1966:202.

14. Israr-ud-Din 1967: 47.For recent extensions of the road network and the planned tunnel project underneath the Loari Pass,cf.Israr-ud-Din 1967:47-48;Amir Mohammed 1981:10-15;Haserodt 1989:141-46.

References

Manuscript and Primary Printed Sources

Ghufran, Mirza Mohammad.1962.A New History of Chitral (Urdu, English translation 1974 in manuscript). Peshawar.IOL/P&S/12/3246: India Office Library &Records: Departmental Papers: Political & Secret Internal Files & Collec-tions 1931-1947:Chinese Turkestan: Trade: Development of Trade between India and Chinese Turkestan. Letter of P.A. Gilgit 30.4.1928.

IOR/2/1076/232: India Office Records: Development of Trade between India and Chinese Turkestan. File No 22-C of 1938.

Lockhart, W.S.A. & R.G. Woodthorpe.1889.The Gilgit Mission 1885-86.London.

1894.Report on the Baroghil-Mastuj-Chitral Route. Gilgit (Public Record Office/FO 539/67:pp.28-29).1895. The Northern Frontier of India. Roads and Passes. Measures for Defence of Frontier. London(IOL/P&S/18/A 95).

Secondary Printed Sources

Amir Mohammed,ed.1981.Agriculture Experts Committee Report on Chitral. Islamabad.

Barth,Fredrik. 1956. Indus and Swat Kohistan-An Ethnographic Survey, Studies Honouring the Centennial of Universtetets Etnografiske Museum,Oslo 1857-1957; Vol.Il:pp.5-98.Oslo.

Beg. R.K. 1990. Revenue System of the Ex-state of Chitral. Terich Mer 5:pp.5-6.12.

Biddulph,John 1880. Tribes of theHindoo Koosh. Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing.

Reprints, edited by K. Gratzl, Graz: Akademische Druck-u. Verlagsanstatlt, 1971; Karachi:Indus Publications.1977.

Dichter,D.1967.The North-West Frontier of West Pakistan. A Study in Regional Geography. Oxford.

Eggert, P. 1990. Die frühere Sozialordnung Moolkhos und Turkhos (Chitral). (Beiträge zur Südasienforschung134.Stuttgart.

Faizi,Inayatullah 1991.The Geo-political Significance of the Southern Passes of the Wakhan Corridor. Unpublished dissertation,Peshawar.

Harris,L.1971.The Frontier Route from Peshawar to Chitral: Political and Strategic Aspects of the ‘Forward Policy’1889-1896.Contributions to Asian Studies I:pp.81-108.

Haserodt, K. 1989. Chitral (Pakistanischer Hindukusch).Strukturen, Wandel und Probleme eines Lebensraumes im HochgebirgezwischenGletschernundWüste.In Hochgebirgsräume Nordpakistans im Hindukusch, Karakorumund Westhimalaya, ed. K. Haserodt. pp. 43-180. Beitrüge und materialien zur Regionalen Geographic, 2. Berlin:TU Berlin.

Holzwarth,Wolfgang. 1990. Vom Fürstentum zur afghanischen Provinz. Badakhshan 1880-1935.Berlin.

Israr-ud-Din.1967.Socio-economic Developments in Chitral State.Pakistan Geographical Review 22 (1):pp.42-51.Kreutzmann,H.1995.Globalization,Spatial Integration,and Sustainable Development in Northern Pakistan.Mountain Research and Development 15(3): pp. 213-27.

Lorimer,David Lockhart Robinson. 1980. Personal records from the India Office Library & Records. Edited and published by I.Müller-Stellrecht: Materialien zur Ethnographie von Dardistan (Pakistan). Aus den nachgelassenenAuf: eichnungen von D.LR. Lorimer. Teil II-11I. Gilgit. Chitral und Yasin. BergvölkerimHindukuschund Karakorum 3.Graz:Akademische Druck-u. Verlagsanstatt.

Malleson. W. 1907. Frontierand Overseas Expeditions from India. Selections from Govt. Records. Vol. 1: Tribes North of the Kabul River. Simla. Reprint, Quetta, 1979.

Morgenstierne, G. 1932. Report on Linguistic Mission to North-Western India. Instituttet for Sammenlignende Kulturforskning. C III-1. Oslo. Reprint, Karachi: Indus Publications, no date.

Power, R.H. 1948. A Subaltern in the Gilgit Agency. The Royul Engineers Journal 62(1):pp.66-77.

Proudlock, V. 1947. By Jeep to Chitral. Journal of the Royal Central Asian Society 34 (2): pp. 193-94.

Schomberg,ReginaldC.F. 1938. Kafirs and Glaciers. Travels in Chitral. London.

Skrine. C.P. 1925. The Roads to Kashgar. Journal of the Royal Central Asian Society 12:pp.226-50.

Staley, J. 1966. Economy and Society in Dardistan: Traditional Systems and the Impact of Change. Lahore.

About the author: Prof. Hermann Kreutzmann held the Chair of Human Geography at Freie Universitaet Berlin until March 2020. His main research interest is regionally located in Central and South Asia with Pakistan and its neighbours as the prime focus; the topics range from development studies, high mountain research, mobility and migration to political geography and minority issues. Empirical research has been implemented since more than 40 years resulting in more than 25 books and 250 plus published research papers.

Uploaded on 4 October 2024